Difficulty of AP Calculus: Is the AB Exam Hard?

The AB Exam is moderately difficult. If we place the exam on a 1 to 10 scale, AP Calc AB exam would be on the 5.5 mark with 60-64% scoring a 3 or higher. 64% is lower than the average passing rate for all AP tests. Out of nearly 30 of the AP classes taken by a huge number of students, AP Calculus AB ranks as the 12th most difficult thus indicating it has earned its place as a difficult AP test.

When we observe the concepts covered, we discover that they are college-level. There exists new ideas such as: limits, derivatives, and integrals. These topics will require absolute discipline to completely understand and continuous practice and the need for this heavily contributes to the Calc AB Exam’s difficulty.

From a test taking perspective, it isn’t just a question of how frequently you practice the questions that are repeatedly asked but how well you can think outside the box if something abnormal pops up. In other words, do you have strong problem-solving and critical thinking skills?

Extra Topics Covered in the AP Calculus BC Exam Beyond AB

Infinite Sequences and Series

Infinite Sequences

This section involves finding numbers in a sequence that never ends while approaching a limit (the final destination). When learning about infinite sequences, you will understand what a convergence is and how to derive formulas from the sequences provided to then calculate the nth term in the sequence.

You want to pay very close attention to how you derive formulas. The process involves always making sure the position of the term (n) always has a place in your formula. For example, when we consider 2, 4, 8, 16, 32… as our sequence, it is easy to jump to 64 because you will simply multiply 32 with 2 to give you 64 but getting a formula from the answer you have provided is where the difficulty of the AP Calc BC exam comes into play. The trick is to always make sure the position of the term leads you to the 64 or any other number in the sequence. In our case, the position of the number 64 is 6. Therefore, how do we use 6 (n) to arrive at 64? We have it as a power to 2 with 2 being our constant. The formula then becomes 2n. So, an =2n.

Infinite Series

To refresh your memory, an infinite series is what you get when you add up all the numbers in an infinite sequence. The addition is endless as it has no end but the convergence (a number which the addition approaches but never actually equals) is very real. The opposite of convergence is divergence and here, the series doesn’t approach a finite number but keeps growing bigger and bigger. A very good example of a divergence is 1+2+3+4+5+… = Infinity.

Parametric Equations, Polar Coordinates, and Vector-Valued Functions

Parametric Equations

These are what make it possible to draw figure 8’s and vertical lines on graphs. They simply involve t (time) describing both x and y. This allows for multiple y values to exist with one x value because x and y aren’t dependent on each other like in y=f(x) but on t.

Some of the key ideas involving parametric equations are slopes. Calculating slopes for parametric equations involves the formula:

dy/dx = dy/dt divided by dx/dt.

Example:

X = x(t) = t2

dx/dt = d (tn)/dt = n multiplied by tn-1.

d (t2))/dt = 2 multiplied by t2-1.

= 2t

Y = y(t) = t3

dy/dt = d (tn)/dt = n multiplied by tn-1.

dy/dt = d (t3)/dt = 3 multiplied by t3-1.

= 3t2

dy/dx = dy/dt divided by dx/dt = 3t2 divided by 2t = 3t/2

Slope = 3t/2

I am going to be honest with this. Placing d (tn)/dt complicates things and is honestly unnecessary. It is clearer to simply stick to dy/dt and dx/dt and simply remember the formula n multiplied by tn-1. The formula is how you find the change in y and change in x when t (time) is changing and you have the values of y(t) and x(t).

Polar Coordinates

Polar coordinates represent a comprehensive assessment of cumulative calculus fluency within the AP Calculus BC framework. The successful navigation of polar problems relies less on novel conceptual leaps and more on the accurate application of prerequisite skills—specifically, the product rule, the chain rule, the Extreme Value Theorem, and definite integration—transferred into a non-Cartesian coordinate system.

The complexity of polar free response questions demands that students transition from rote memorization of formulas to a systematic, analytical approach based on deriving the complex expressions from the foundational parametric equations, x=rcosθ and y=rsinθ.

Procedural mastery of this derivation provides the solution mechanism for computing slope, locating tangents, optimizing coordinates, and solving kinematic rates problems.

Furthermore, since integration setup, particularly the determination of angular limits, depends heavily on geometric visualization and identifying intersection points, proficiency in graphing and analyzing polar curves is a prerequisite for achieving accuracy in integral applications. Polar calculus ultimately confirms the student’s ability to synthesize and apply advanced differential and integral techniques under complex, geometrically dependent constraints.

More Advanced Techniques of Integration

The AP Calculus BC curriculum requires mastery of several integration techniques not covered in AP Calculus AB. These methods are essential for integrating a wider variety of functions, particularly products of functions and rational functions.

The three primary advanced techniques are:

Integration by Parts

- Concept: This technique is essentially the reverse of the Product Rule for differentiation. It’s used to integrate the product of two different types of functions (e.g., a polynomial and an exponential function).

- Formula:

∫udv=uv−∫vdu - Strategy: The key is choosing the parts u and dv correctly. A common mnemonic for prioritizing the choice of u is LIATE (Logarithmic, Inverse Trigonometric, Algebraic, Trigonometric, Exponential). The function chosen for u should generally be one that simplifies when differentiated, while dv should be easily integrable.

Integration by Partial Fractions

- Concept: This method is used to integrate rational functions (a polynomial divided by a polynomial) by decomposing the fraction into a sum of simpler fractions.

- Strategy:

- Ensure the rational function is a proper fraction (degree of numerator < degree of denominator). If not, use polynomial long division first.

- Factor the denominator completely.

- Set up the partial fraction decomposition based on the factors (linear factors, repeated linear factors, irreducible quadratic factors, etc.).

- Solve for the unknown coefficients in the decomposition.

- Integrate the resulting simpler fractions, which often involve natural logarithms or inverse trigonometric functions.

Improper Integrals

- Concept: These are definite integrals where the interval of integration is infinite or where the integrand has an infinite discontinuity (a vertical asymptote) within the interval.

- Strategy: Improper integrals are evaluated by replacing the problematic limit with a variable and evaluating the integral as a limit.

- Infinite Interval: For ∫a∞f(x)dx, you evaluate it as limb→∞∫abf(x)dx.

- Infinite Discontinuity: For ∫abf(x)dx where f(x) is discontinuous at x=c in [a,b], you evaluate it as limk→c−∫akf(x)dx+limk→c+∫kbf(x)dx.

- Convergence and Divergence: If the limit exists and is a finite number, the improper integral converges to that number. If the limit is ±∞ or does not exist, the integral diverges.

Arc Length and distance along curves

The AP Calculus BC course expands the application of definite integrals to find the distance along a curved path. This is covered for functions in Cartesian coordinates, parametric equations, and vector-valued functions.

Arc Length for y=f(x)

- Concept: The arc length is the distance traveled along a function’s curve between two points. It’s derived by applying the Pythagorean Theorem (ds2=dx2+dy2) to infinitesimally small segments (ds) of the curve and integrating.

- Formula (Cartesian): For a smooth curve y=f(x) from x=a to x=b:

Distance Traveled for Parametric Curves and Vectors

In BC, a significant application of arc length is finding the total distance traveled by a particle whose motion is described by a set of parametric equations or a vector-valued function.

- Parametric Equations: If the position of a particle is given by x(t) and y(t) for t1≤t≤t2, the distance traveled is the arc length of the path traced out.

- Vector-Valued Functions: If the velocity of a particle is given by the vector v(t)=⟨x′(t),y′(t)⟩, the speed of the particle is the magnitude of the velocity vector:

- Formula (Parametric/Vector): The total distance D traveled from time t=a to t=b is the integral of the speed:

What Determines the Difficulty of AP Calculus AB and BC Exams?

The difficulty of AP Calculus AB and BC stems from two key factors: curriculum scope and the academic caliber of students who take each exam.

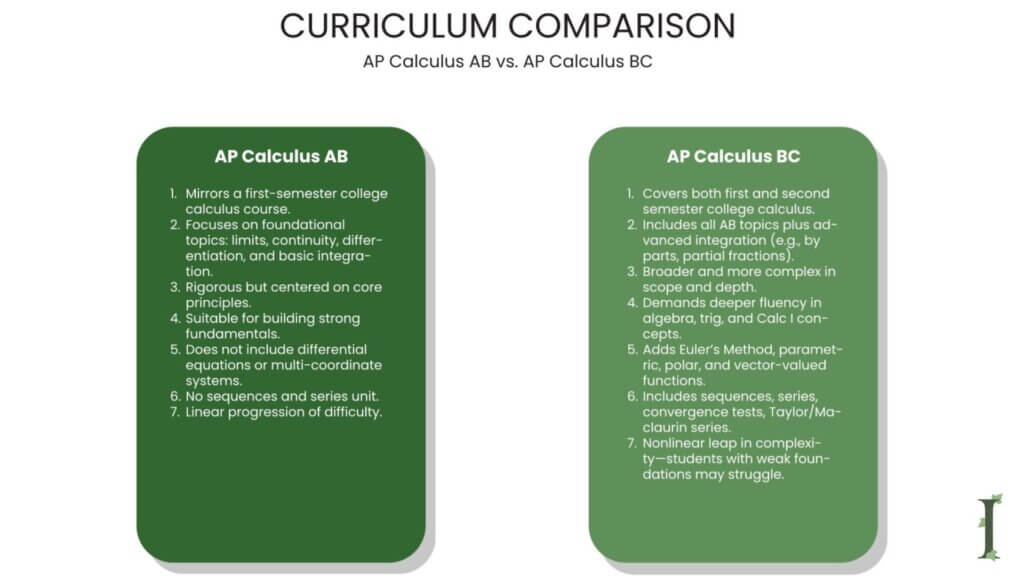

Curriculum Comparison: Calculus I vs. Calculus I & II

AP Calculus AB mirrors a first-semester college calculus course (Calculus I), covering foundational topics like limits, continuity, differentiation, and basic integration. It’s rigorous but focused on core principles.

AP Calculus BC, however, encompasses both Calculus I and II, making it significantly broader and more complex. Beyond AB’s content, BC dives into advanced integration techniques (e.g., integration by parts, partial fractions), differential equations (Euler’s Method), and multi-coordinate systems (parametric, polar, vector-valued functions). Its most challenging unit—sequences and series—requires mastery of convergence tests and Taylor/Maclaurin series, demanding deep fluency in algebra, trigonometry, and Calc I fundamentals.

This leap in complexity isn’t linear. Students with weak foundational skills often struggle disproportionately with BC’s abstract and layered concepts.

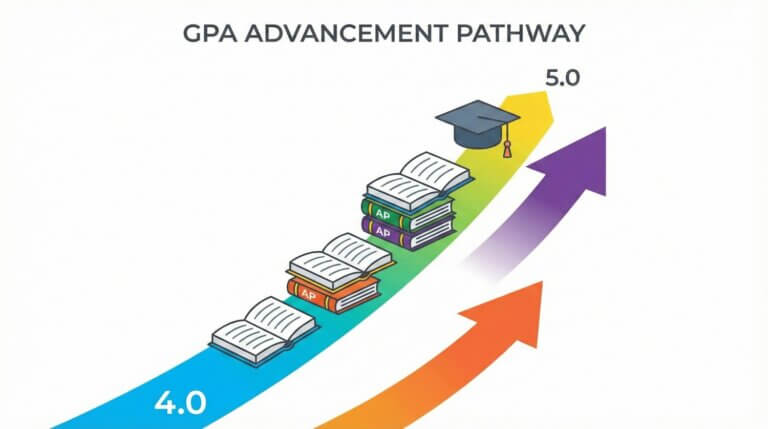

The Statistical Paradox: Why BC Scores Are Higher

Despite its tougher content, AP Calculus BC consistently yields higher scores. In 2025, 44% of BC students earned a 5, compared to just 20.3% in AB. This isn’t because BC is easier—it’s due to selection bias.

BC students are typically more advanced, having completed rigorous math prerequisites and often being years ahead in their studies. They’re high-achieving, motivated learners aiming for STEM fields like engineering or computer science. Their preparation and aptitude allow them to excel in BC’s demanding curriculum.

Exam Structure Breakdown: AP Calculus AB and BC Exam Formats Explained

Both AP Calculus AB and BC exams share a nearly identical structure, designed to assess both conceptual understanding and procedural fluency. Each exam lasts 3 hours and 15 minutes and is split evenly into two sections: Multiple Choice (MCQ) and Free Response (FRQ), each contributing 50% to the final score.

Section I: Multiple Choice (45 Questions, 1hr 45min) This section is divided into two parts based on calculator usage:

- Part A (30 questions, 60 min): No calculator allowed. Focuses on core calculus skills—limits, derivatives, integrals, and algebraic manipulation.

- Part B (15 questions, 45 min): Graphing calculator required. Tests applications like numeric derivatives, definite integrals, and solving equations. Questions span algebraic, exponential, logarithmic, and trigonometric functions in various formats (graphical, tabular, verbal).

Section II: Free Response (6 Questions, 1hr 30min) Also split by calculator policy:

- Part A (2 questions, 30 min): Calculator required. Emphasizes real-world applications and multi-step problem solving.

- Part B (4 questions, 60 min): No calculator. Tests manual precision and deeper conceptual reasoning.

Each FRQ is scored on a 9-point scale, with partial credit awarded for correct methods—even if the final answer has minor errors. This encourages students to show their work and demonstrate understanding.

Calculator Strategy Matters Success on both exams requires fluency with approved graphing calculators (Casio, HP, TI models). Students must master four key operations: solving equations, numerical differentiation, numerical integration, and graphing. However, over-reliance on technology can backfire—non-calculator sections demand strong algebraic and conceptual skills.

Exam Pass Rates and Trends: AP Calculus AB and BC Exam Pass Rate and Mean Scores

An examination of recent score distributions reveals stable performance trends and the profound importance of the Calculus BC AB subscore as an evaluative metric.

A. Longitudinal Performance Analysis (2019–2025)

The data consistently demonstrates that the Calculus BC cohort significantly outperforms the AB cohort across all metrics. The rate of achieving a score of 3 or higher (3+), generally accepted as passing by colleges, is consistently above 75% for BC test-takers.

For instance, the mean score for BC in 2024 was 3.92, with 47.7% achieving a score of 5. For AB in the same year, the mean score was 3.22, and the 5-rate was 21.4%. Even during the volatile testing year of 2021, the BC mean score stood at 3.62, compared to the AB mean score of 2.77. The 2025 results confirmed this trend, with the BC mean score at 3.82 and 78.6% scoring 3+. This persistent statistical disparity, where the BC cohort outperforms the AB cohort, results from the rigorous selection criteria and advanced mathematical background of the students who enroll in Calculus BC.

B. Analysis of the Calculus BC AB Subscore

The AB subscore is a highly advantageous feature of the BC exam, as it calculates a separate score based only on the Calculus AB content, which constitutes approximately 60% of the entire BC examination. This metric is used by colleges to grant advanced standing or credit for the first semester of calculus.

Performance on the AB subscore is typically the highest of all calculus metrics. In 2024, the AB subscore achieved a global mean of 4.16, with 50.1% of BC test-takers earning a score of 5 on this portion. This remarkably high achievement level confirms that BC students possess exceptionally robust mastery of the fundamental Calc I curriculum before moving onto the more challenging Calc II content.

Colleges are advised to treat the AB subscore identically to a standalone AP Calculus AB exam score. This is a strategic advantage for students, providing a crucial safety net. If a BC student struggles specifically with the advanced Calc II material (e.g., series), they can still rely on a high AB subscore to demonstrate mastery of Calculus I, thereby securing essential college credit for the first semester of university mathematics.

How to Study for the AP Calculus AB Exam: Proven Strategies to Boost Exam Pass Success

Effective preparation for the AP Calculus exams requires adopting strategies that extend beyond calculation, focusing on conceptual justification and addressing documented communicative gaps observed in official scoring reports.

A. Strategic Pillars for Exam Success

The development of successful examination skills relies on three strategic pillars:

- Mastery of Fundamentals: Students must ensure non-negotiable proficiency in all foundational derivative and integral rules. This fundamental knowledge is prerequisite for moving toward applications; attempting advanced problems without core fluency will impede overall comprehension and speed.

- Dedicated Non-Calculator Practice: Given that significant portions of the exam forbid calculator use, students must consistently practice algebraic manipulation and calculus procedures manually. This practice must simulate exam timing to build endurance and efficiency, ensuring that conceptual understanding remains robust without technological assistance.

- Review of Official Materials: The College Board maintains consistent question styles, particularly in the Free-Response Questions. Thorough review of past FRQs and their scoring guidelines is essential for maximizing familiarity with expected solution structures and justification requirements.

B. Addressing Common Pitfalls: The Communicative Gap

Chief Reader Reports from the College Board consistently highlight that many points are lost due to issues in mathematical communication and contextual interpretation rather than calculation errors.

The Requirement for Precise Justification Students must articulate the why behind their mathematical steps. This includes explicitly stating the preconditions of theorems. For example, when applying the Mean Value Theorem (MVT), students must note that differentiability over an interval implies continuity, satisfying the theorem’s requirements.

In the 2024 exam, a common failure was difficulty in using the sign of the second derivative, C′′(t), to formally justify whether the rate of change, C′(t), was increasing or decreasing.

Contextual Interpretation and Unit Accuracy A persistent source of error involves contextual interpretation and unit errors. Students frequently fail to correctly describe the meaning of their results within the problem’s scenario or omit units entirely, particularly in FRQs.

A specific issue identified in the 2023 exam was the misinterpretation of a definite integral, ∫60135f(t)dt, which represents accumulated quantity (gallons), mistakenly interpreted as a rate (gallons per second).

Furthermore, failure to use precise language, such as describing a second derivative as a “rate of a rate,” leads to the loss of interpretation points.

Documentation of Work Even in calculator-active questions, students must explicitly write out the full mathematical setup—such as the limits of integration for a definite integral or the structure of a Riemann sum—before presenting the numerical result obtained from the calculator.

Skipping this written setup, often referred to as “showing sufficient work,” is a frequent reason for point deduction.

Table Title: Pedagogical Focus: Key AP Calculus Content Areas and Common Errors

| Content Topic | Required Conceptual Skill | Common Student Error |

| MVT and Rolle’s Theorem | Explicitly stating continuity/differentiability preconditions. | Applying theorems without verifying initial conditions; providing insufficient justification for existence. |

| Integrals/Accumulation | Interpretation of definite integrals and Riemann sums in context. | Confusing the meaning of an integral (quantity) with the derivative (rate); inadequate written setup for Riemann sums. |

| Applied Rates | Interpreting dx2d2y and analyzing speed/acceleration. | Incorrect units (e.g., omitting units/(time)2); failure to use the sign of a(t) to analyze speed. |

| Technology Use | Showing mathematical setup for calculator procedures. | Providing only the numerical result without showing the mathematical expression integrated or differentiated by the calculator. |

C. Review Resource Optimization

Optimal study preparation is multilayered, combining different types of resources. Students benefit from using comprehensive review books for deep coverage of theorems, complemented by strategy guides that offer structured study plans (e.g., 5-, 10-, and 20-week plans) and effective exam hacks.

The integration of official College Board materials, especially past FRQs, ensures that practice aligns with the expected difficulty and style of the actual examination.

2025 Exam Data on AP Calculus AB and BC: Insights into Exam Pass Rates and Difficulty

The 2025 score distributions offer current data points that confirm the established difficulty structure and student performance levels for both AP Calculus exams.

A. Interpreting the 2025 Results

The performance data for 2025 demonstrates continuity with the trends observed in previous years:

- AP Calculus BC 2025: The exam saw 160,436 students tested. The 5-rate reached 44.0%, with 78.6% of all test-takers achieving a score of 3 or higher. This strong showing confirms the highly successful performance profile of the BC cohort and indicates the exam was calibrated to its historical difficulty standard.

- AP Calculus AB 2025: The exam recorded a 5-rate of 20.3% and an overall pass rate (3+) of 64.2%. This score profile, while statistically lower than BC, is slightly higher than the pandemic-affected 2021 scores (17.6% 5-rate).

B. Difficulty Projection for 2026

AP exams are criterion-referenced assessments, meaning the resulting scores are calibrated to specific performance standards equivalent to college course grades.

The consistent statistical gap of approximately 0.7 to 1.0 mean score points between AB and BC demonstrates that the College Board successfully maintains distinct difficulty benchmarks for the two exams, reflecting the known disparity in student preparation.

Therefore, students preparing for the 2026 examination cycle should anticipate a difficulty level that aligns closely with the established 2025 benchmarks. The required raw score necessary for achieving the top score of 5 will be rigorously calibrated based on this consistency.

Students aiming for high scores, particularly on the BC exam, must target performance levels that significantly exceed the historical minimum raw scores to secure a competitive advantage within this high-achieving peer group.

College Perspectives on Taking AP Calculus AB and BC: Alumnae Experiences and Advice

The choice between AP Calculus AB and BC functions as a critical component of a student’s academic profile, influencing both admission evaluation and subsequent college placement.

A. Admissions Signaling and Course Rigor

For students seeking admission to competitive universities, particularly those with strong emphasis on engineering, computer science, or mathematics, AP Calculus BC carries superior weight.

Admissions officers are required to evaluate a student in the context of their available academic opportunities. Generally, a student who pursues AP Calculus BC signals a commitment to the most rigorous academic schedule available compared to a peer who concludes their high school calculus study with AB.

The fundamental advice for maximizing college prospects is to select the course that provides the greatest challenge without unduly risking the potential for success. For mathematically proficient students who meet the prerequisites, BC is invariably the preferred option for signaling preparedness for advanced quantitative university coursework.

B. Credit and Placement Policy Disparity

University policies regarding AP Calculus scores vary widely, ranging from institutions that accept a score of 3 for basic credit to highly selective schools demanding a 5 for placement.

Credit for Requirements Fulfillment Many institutions are generous in awarding credit for general requirements. For example, UC Berkeley grants subject credit for Math 1A (first-semester calculus) for any score of 3, 4, or 5 on AP Calculus AB. Similarly, Mount Saint Vincent grants four credits and fulfills the Mathematics core requirement for a score of 3 or higher on the AB exam.

Placement at Selective Institutions At technically focused or highly competitive universities, the score is primarily utilized for advanced placement, allowing students to bypass introductory courses and enroll immediately in subsequent, higher-level classes.

The policy at the University of California, Berkeley demonstrates a strong incentive for taking BC: a score of 5 on the BC exam grants credit for both Math 1A and 1B, covering a full year of calculus.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) enforces the most stringent policy. MIT requires a score of 5 on any AP exam for credit consideration. Specifically, a score of 5 on the Calculus AB exam does not grant credit but only permits enrollment in the accelerated calculus sequence (18.01A/18.02A).

To earn credit for 18.01 (Single-variable Calculus), a student must obtain a score of 5 on the Calculus BC exam.

This stringent MIT policy underscores that for elite technical schools, the AP score acts fundamentally as a placement tool.

The institution verifies whether the student’s high school preparation is sufficient to skip their introductory sequence and immediately handle the conceptual rigor of subsequent mathematics courses. For students targeting these top-tier programs, achieving a 5 on Calculus BC is essential to optimize their academic progression and maximize advanced placement opportunities.